The Question Everyone Is Asking (But Asking Wrong)

Is Agile dead?

It’s a question that keeps resurfacing—usually after another sprint that felt busy but strangely unproductive, or another planning session that reopened debates everyone thought were settled months ago. The takes are familiar and increasingly polarized. Some argue Agile just needs to be “done right.” Others declare it broken, outdated, or actively harmful.

Both sides miss the point.

Recently, I argued in a separate piece that the hardest part of software development no longer lives in code, but in the specification—where intent is captured, irreversible decisions are made deliberately, and machines are given something precise to execute against (see: Why the Hard Part of Coding No Longer Lives in Code).

That argument leads directly to the question behind the question.

The real issue isn’t whether Agile works. In many contexts, it clearly does. The more important question is why Agile existed in the first place—and whether the constraint it was designed to address still defines the limits of how software gets built.

This isn’t a takedown of Agile or a call to return to waterfall. It’s a diagnosis. Agile was a rational response to a specific set of human limits. What’s changing now isn’t the desire to move fast or learn continuously. It’s the nature of the constraint itself.

Agile as a Rational Response to Human Limits

To understand why the question of Agile’s relevance matters, it helps to remember what Agile was actually solving.

Agile didn’t emerge because teams disliked planning or documentation (OK—admittedly, we hate it a little). It emerged because humans are cognitively constrained, and traditional software processes routinely ignored those constraints. Large systems were too complex for any individual or small group to reason about end-to-end. Requirements documents grew so large and interdependent that they were no longer meaningfully comprehensible. Decisions made months in advance were often wrong by the time code was written. The cost of being precise early was high—and the penalty for being wrong was even higher.

Under those conditions, deferring decisions was often the least bad option.

Agile optimized for a world where researching, reasoning, validating and writing were slow and expensive. Short specs, user stories, and incremental delivery reduced the amount any single person had to hold in their head. Frequent feedback loops compensated for limited foresight. “Inspect and adapt” wasn’t a slogan—it was a survival strategy.

Crucially, Agile also assumed that deep research, rigorous reasoning, and comprehensive validation up front were impractical. Writing long, well-researched specifications took too much time. Exploring multiple design paths was costly. Validation required real users, real code, and real delays. Iteration wasn’t just faster—it was the only economically viable way to learn.

Agile didn’t just respond to slow execution; it responded to genuine uncertainty. What’s changed is not that uncertainty vanished, but that the cost of exploring it before commitment has collapsed.

Given those constraints, Agile wasn’t sloppy. It was pragmatic.

The Constraint That Quietly Disappeared

What’s changed isn’t our appetite for speed or our tolerance for uncertainty. What’s changed is the cost structure of thinking.

Until very recently, deeply researching a problem, reasoning through multiple system designs, documenting intent precisely, and validating ideas before implementation were all slow, labor-intensive activities. They required scarce human time and coordination across roles. In that world, deferring decisions wasn’t a failure of discipline—it was often the only practical option.

That constraint has quietly but decisively weakened.

Agentic research systems can now survey prior art, standards, competitors, and edge cases in hours rather than weeks. Reasoning and synthesis—once the bottleneck of senior engineers and product leads—can be externalized and iterated collaboratively with AI. Writing and maintaining large specifications is no longer a heroic act; it’s mechanically cheap. Even validation has shifted, with agent-based simulations allowing teams to test workflows, onboarding flows, and UI decisions against synthetic users long before real code ships.

The result is a fundamental inversion. It is now trivial—not exceptional—to produce a deeply researched, reasoned, and at least synthetically validated specification. Documents that would once have been dismissed as impractically long—three hundred pages, five hundred pages—are no longer a burden when they’re generated, structured, and consumed by machines.

What used to be “too slow to think through up front” is no longer slow at all. The limiting factor is no longer research or documentation cost. It’s whether teams are willing to commit intent when doing so has become cheap.

The question is no longer whether uncertainty exists, but how cheaply and deliberately it can be explored—now that AI has collapsed the cost of research, reasoning, and validation—before decisions harden.

When the Constraint Vanished—but the Process Stayed

As the original constraint disappears, Agile hasn’t meaningfully adapted in most organizations. Instead, it lingers—often awkwardly—long after the conditions that justified it have begun to erode.

The rituals remain even as the economics change. Standups, sprints, backlogs, and retrospectives continue to structure work—but increasingly without the constraint they were designed to manage. What was once a pragmatic response to human limits has slowly hardened into habit, then into doctrine.

This is where Agile drifts.

Practices that were meant to buy time for learning now excuse the absence of decisions. Deferring commitment is still framed as “flexibility,” even when the information needed to decide is already available. Ambiguity persists not because reality is unknowable, but because resolving it feels culturally risky.

The pattern becomes familiar:

Decisions deferred under the banner of “flexibility.” Requirements “rediscovered” in code rather than deliberately specified. The same debates replayed every sprint. Ambiguity masquerading as adaptability.

What emerges isn’t agility—it’s Agile Theater.

Agile Theater looks productive from the outside. Work is visible. Tickets move. Velocity charts trend upward. Demos happen on schedule. But underneath the motion, the system never quite converges. Irreversible decisions are made implicitly—by whichever implementation happens to land first—rather than explicitly, with intent and accountability.

In this form, Agile stops being a learning system and becomes a moral shield. Not deciding is reframed as humility. Writing things down is dismissed as premature. Commitment is treated as overconfidence. The result is not adaptability, but drift—masked by ceremony and sustained by the comfort of constant motion.

The Cost of Agile Theater in an AI World

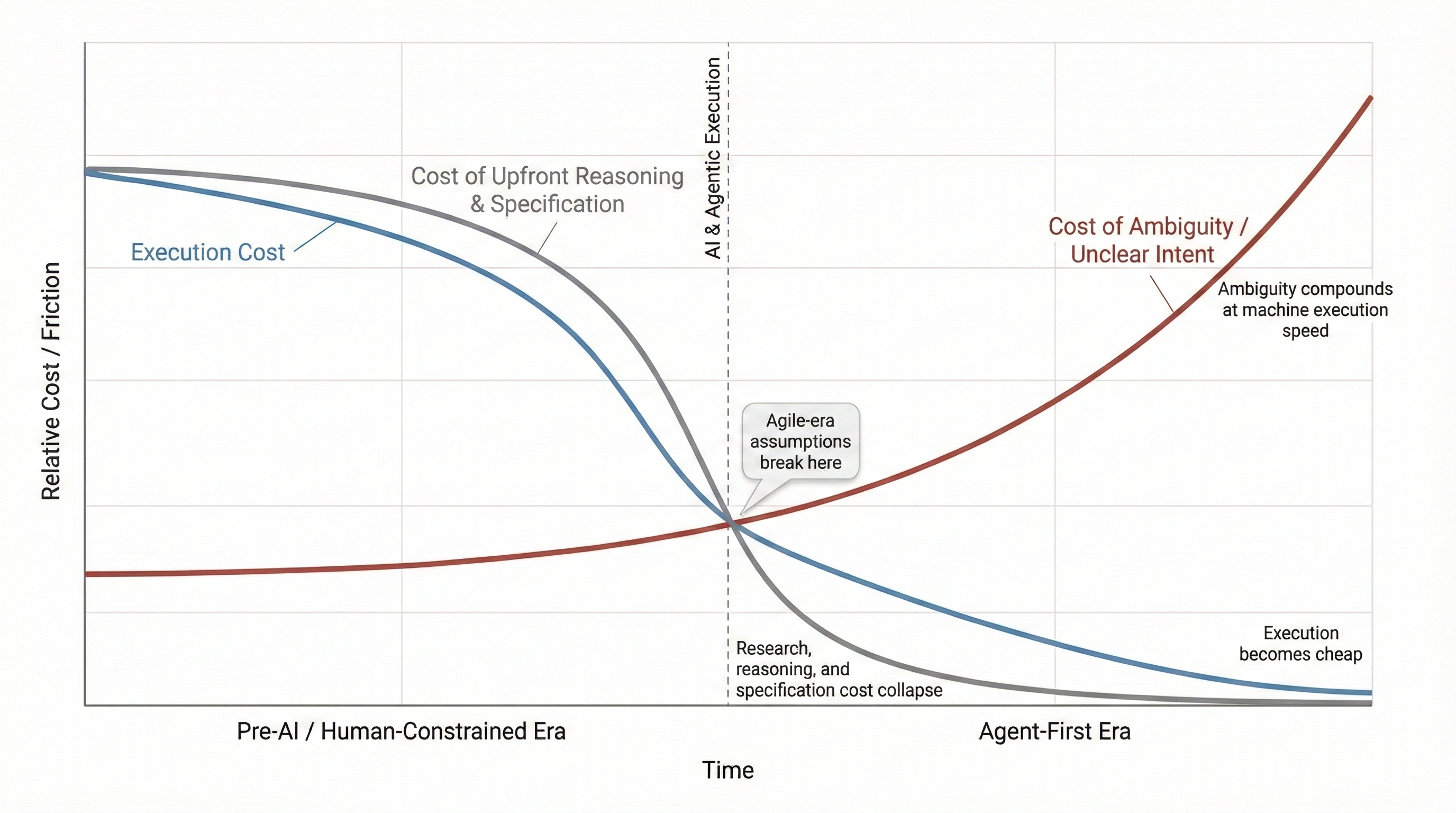

Figure 1: Cost Curve Inversion in an Agent-First World

As AI collapses the cost of execution and upfront reasoning, ambiguity becomes the dominant—and compounding—risk. Processes designed for a world where thinking was expensive no longer protect teams when speed turns unclear intent into irreversible structure.

In an agent-first world, speed itself becomes the hazard. Execution no longer acts as a natural brake on bad decisions—it accelerates them. When development moves at human speed, ambiguity has time to surface, be debated, and corrected. When development moves at machine speed, ambiguity doesn’t slow things down—it compounds.

Decisions that once would have been revisited sprint after sprint now harden into systems before anyone realizes they were made at all. Speed without intent doesn’t just fail faster. It multiplies risk.

In a pre-AI world, Agile Theater was mostly inefficient. In an AI-augmented world, it’s actively dangerous.

The reason is simple: ambiguity scales differently than execution.

Modern coding agents are extraordinarily good at moving forward. They don’t tire, they don’t hesitate, and they don’t ask whether a vague requirement reflects deliberate judgment or accidental omission. When intent is unclear, agents don’t slow down—they fill in the gaps. And once those gaps are filled with working code, the decisions harden quickly, often without anyone consciously choosing them.

This is where Agile Theater quietly accumulates risk.

Specs fragmented across tickets, comments, and commits stop being a shared source of truth. Core assumptions drift as features are added sprint by sprint. Architectural choices emerge implicitly from local optimizations rather than global intent. By the time a team realizes something fundamental has been decided—about data models, workflows, permissions, or extensibility—it’s already expensive to unwind.

What looks like adaptability is often just decision-making deferred until reversal is painful.

AI accelerates this failure mode because it collapses execution time without collapsing ambiguity. Teams feel faster than ever, but they’re also more likely to outrun their own intent. The system grows rapidly, but not necessarily coherently. Velocity increases while alignment decays.

The paradox is that Agile Theater feels most comfortable precisely when it’s most costly. As long as progress is visible and incremental, there’s little pressure to stop and ask whether the right decisions have actually been made. But in an environment where agents can generate weeks of implementation in hours, the penalty for unclear intent compounds far faster than it ever did before.

In an AI-first world, ambiguity isn’t a temporary state to be resolved later. It’s a multiplier.

What Replaces It: Intentional Commitment, Not Waterfall

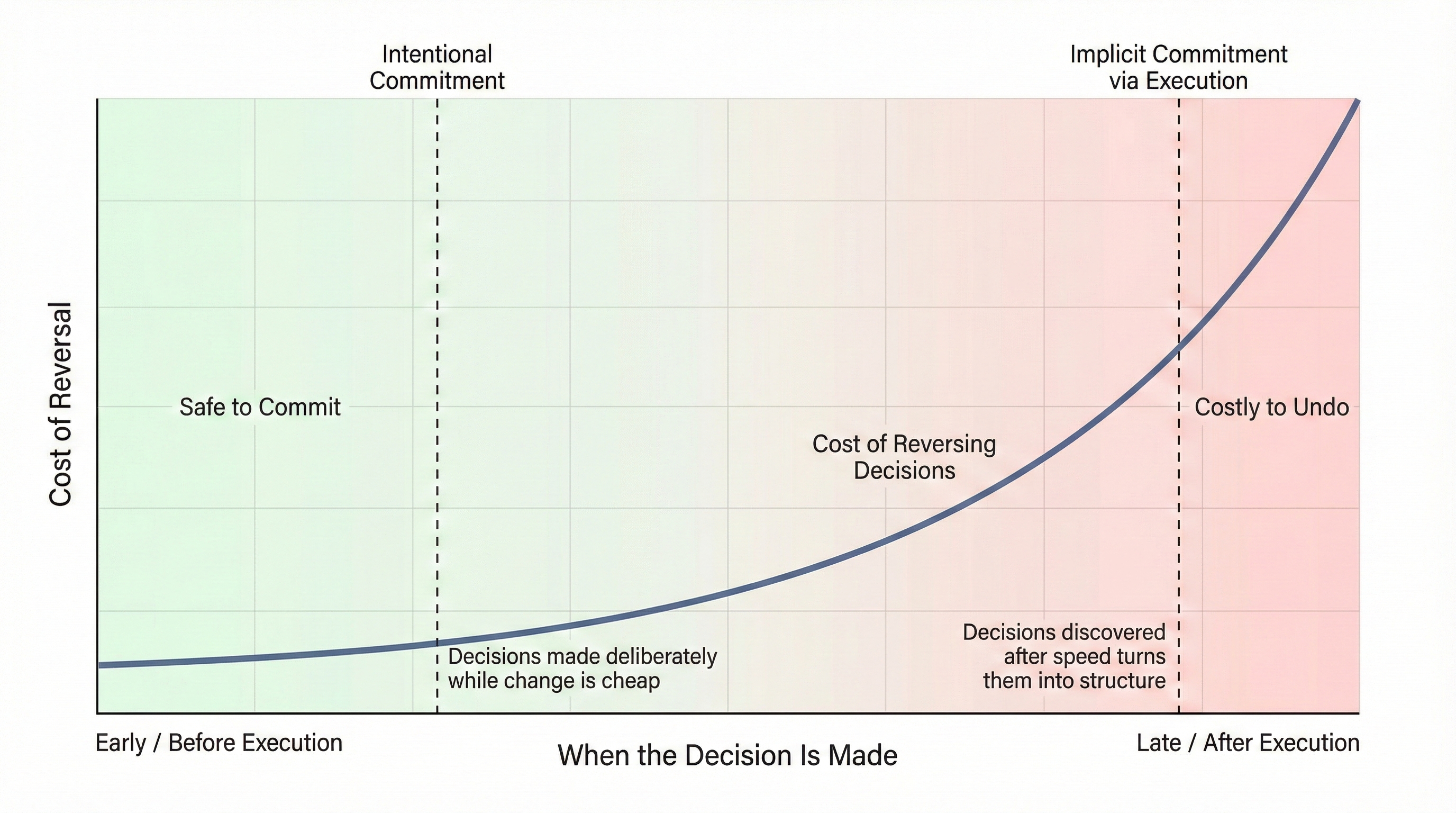

Figure 2: Decision Timing and the Cost of Reversal The later a decision is made, the more expensive it becomes to undo. In an agent-first world, speed turns implicit decisions into structure faster than teams can notice—making deliberate early commitment cheaper than deferral.

At this point, a familiar objection usually surfaces: “This sounds like a return to big design up front.” It isn’t.

What’s being argued for here is not freezing requirements early or pretending uncertainty doesn’t exist. It’s something narrower—and more demanding: making deliberate commitments where reversibility is low, and doing so while commitment is cheap.

Agile implicitly treated most decisions as reversible. In practice, many are not. Core domain models, data shapes, permission systems, workflow assumptions, and product positioning decisions harden quickly. Even when code can be changed, the downstream effects—migrations, user expectations, integrations—often cannot be undone without real cost.

The alternative to Agile Theater isn’t less iteration. It’s better ordering of commitment.

Instead of letting decisions emerge implicitly through implementation, teams identify which choices are genuinely hard to reverse and force clarity there first. Intent is made explicit—researched, reasoned, and documented—before large-scale execution begins. Everything else remains flexible by design.

This creates a different rhythm. Exploration still happens, but it’s front-loaded when AI makes research, synthesis, and validation cheap. Execution still moves quickly, but within boundaries shaped by deliberate judgment rather than accidental drift.

The goal isn’t to predict everything. It’s to decide the few things that matter most—on purpose—before speed turns them into facts on the ground.

That shift doesn’t slow teams down. It removes the need to keep rediscovering the same decisions sprint after sprint.

So… Is Agile Dead?

Agile isn’t dead. But the version of Agile that survives by avoiding commitment should be.

Agile as a mindset—iterative learning, responsiveness to reality, respect for uncertainty—still matters. Those instincts aren’t obsolete. What’s obsolete is treating human cognitive and economic limits as if they were immutable facts of nature.

Agile was built for a world where deep thinking was slow, documentation was expensive, and being wrong early carried a high penalty. In that world, deferring decisions was often rational. In a world where research, reasoning, writing, and even validation can be done continuously by machines, that justification no longer holds.

What needs to die isn’t iteration. It’s the reflex to confuse not deciding with being adaptive.

Agile doesn’t fail because teams move too fast. It fails when speed is used to outrun intent—when motion replaces judgment, and process replaces responsibility. The future doesn’t belong to rigid plans or endless sprints. It belongs to teams that know when to stay flexible—and when to commit.

The Real Shift: From Managing Humans to Managing Intent

What’s actually changing isn’t Agile, and it isn’t the existence of process. It’s what software development is optimized around.

For decades, our tools and methodologies were designed to manage human limitations: memory, attention, coordination, and time. Agile was one of the most successful expressions of that era. It helped teams move forward despite those limits.

AI changes the center of gravity.

Execution is no longer the scarce resource. Research, synthesis, documentation, and iteration can all happen continuously and cheaply. What remains scarce—and increasingly valuable—is clear intent: knowing what should exist, why it should exist, and which decisions deserve to be made deliberately rather than discovered accidentally in code.

That shift changes the role of process. Instead of coordinating humans around tasks, process now exists to surface, capture, and lock intent at the right moments—especially where decisions are hard to reverse.

In practice, this means specifications stop being passive documentation and become active control surfaces—the place where intent is made explicit before agents turn speed into structure. Not because humans suddenly love incredibly detailed documentation, but because it’s become cheap to research, synthesize, and validate intent—and because machines can reason over it without human cognitive limits.

This doesn’t diminish developers or product teams. It re-centers them on judgment rather than execution. The teams that thrive won’t be the ones with the fastest velocity charts, but the ones that know when to pause, decide, and commit—before speed turns ambiguity into architecture.

Agile helped us survive a world constrained by human cognition. In an agent-first world—where execution is cheap and ambiguity compounds—the winning teams won’t be the most flexible. They’ll be the ones whose adaptability is grounded in intentional commitment.

Teams that don’t make this shift won’t fail loudly—they’ll move faster than ever while quietly locking in the wrong system.