What Changed—and Why It Matters

In a previous essay, Why AI Is Making Knowledge Work Worth Less, I argued that artificial intelligence is inflating the supply of cognitive labor—analysis, drafting, research, design, and recommendation—and that this inflation is already eroding the pricing power of knowledge work itself. The mechanism is straightforward: when supply increases faster than demand, unit value falls. This is not a metaphor; it is basic economics applied to cognition.

That argument was about what is happening to work.

This essay is about what happens next.

Over the past two years, the cost of producing knowledge work has collapsed. Tasks that once required trained professionals and significant time can now be generated quickly and at low marginal cost. This shift is often described as a productivity breakthrough. That description is accurate, but incomplete.

Productivity explains how more gets done. It does not explain where value ends up.

The consequences of knowledge inflation are already visible. Knowledge work is not disappearing, but its leverage is weakening. Roles centered on producing analysis or drafts are under pressure. Organizations are learning to do more with fewer people—not because those people are less capable, but because the work itself is no longer scarce.

Markets do not reward effort. They reward outcomes under constraint.

When cognition becomes abundant, value does not vanish. It migrates—and economic power migrates with it. It moves away from decision-making itself and toward whatever remains scarce, enforceable, and consequential in the system.

The rest of this essay is about identifying where that value goes—and why.

Why This Matters Now

This shift is not abstract.

If you are a knowledge worker, it explains why productivity gains are no longer translating into leverage or pay.

If you are an executive, it explains why AI lets fewer people generate more plans than the organization can realistically execute.

If you are a founder, it explains why features are easy to copy but distribution, permission, and risk absorption are not.

If you are an investor or policymaker, it explains why economic power is concentrating even as capability is democratizing.

Artificial intelligence is not just changing how work gets done. It is changing where economic power accumulates. This essay offers a model for understanding—and anticipating—that shift.

The Claim: Value Does Not Disappear — It Migrates

When technology makes something dramatically cheaper to produce, we tend to think the winners are the ones who made it cheaper. History suggests otherwise.

Markets do not reward the activity that becomes easier. They reward the activity that remains constrained.

This is why productivity gains so often coincide with pressure on wages and margins. As supply increases, competition intensifies. Prices fall. What once commanded a premium becomes table stakes. The value does not disappear, but it shifts away from the activity that has become abundant and toward whatever still limits outcomes.

In earlier eras, those limits were often physical. Land, machinery, and access to capital determined who could produce at scale. As economies digitized, many of those constraints loosened, and knowledge work rose in value. Thinking, planning, and analysis became scarce capabilities, and the organizations that employed them captured disproportionate returns.

Artificial intelligence reverses that logic.

By making cognition cheap and widely available, AI removes scarcity from the cognitive-work layer of many value chains. Drafts, plans, forecasts, diagnoses, and recommendations can now be generated faster than organizations can act on them. The bottleneck moves downstream.

What remains scarce are not ideas, but the conditions required to turn ideas into outcomes. Execution in the real world. Permission to operate. Access to customers and distribution. The ability to absorb risk when things go wrong.

These are not new sources of value. They are old ones that were temporarily overshadowed when knowledge was expensive. AI brings them back into focus.

The central claim of this essay is simple: as knowledge work becomes abundant, economic value migrates to the constraints that govern action and consequence.

Economic value concentrates where decisions stop being cheap to change. In many AI-driven systems this occurs at the point of resource commitment, but irreversibility can bind upstream as well—at the level of inputs, permissions, access, or exclusive rights—where those constraints are fixed before any decision is made.

A Simple Model of Constraint and Value

To understand where value migrates as knowledge becomes abundant, it helps to separate cognitive work from resource commitment—and to be explicit about what happens before outcomes appear.

By cognitive work, I mean the production of decisions, code, designs, analysis, reasoning, documentation, and plans—the symbolic work that turns inputs into intent and direction. This is the work most knowledge professionals recognize as their craft.

Every organization follows a similar progression. Inputs are gathered. Cognitive work is performed. Resources are committed. Outcomes follow. For much of the past several decades, value concentrated in the cognitive layer. Organizations that could reason better, design better systems, or translate intent into working solutions tended to outperform those that could not.

Artificial intelligence changes that balance.

By dramatically lowering the cost of producing cognitive work—drafts, analyses, recommendations, diagnoses, code, and design artifacts—AI removes scarcity from that layer. Cognitive output can now be generated faster than organizations can commit real resources.

This does not mean that all cognitive work becomes worthless. Some forms of cognition remain scarce because they are tied to trust, accountability, context, or authority. High-stakes judgment, institutional navigation, and decision-making under consequence do not behave like interchangeable drafts.

The claim here is narrower and more precise: as reproducible cognitive output becomes abundant, it loses pricing power. Value migrates toward the constraints that govern whether and how that output can be acted upon.

I’ll refer to this stage as resource commitment. Cognitive work is largely reversible and now very inexpensive to redo. Resource commitment is not. It is the point at which options collapse into consequences.

This is the quiet but important insight:

Markets price downside exposure, not just upside contribution.

Who gets paid more?

- The person who suggests a decision?

- Or the person who signs it, funds it, deploys it, insures it, or is legally and financially liable for it?

That difference is irreversibility—the point where decisions stop being cheap to change and outcomes become real.

This explains:

- Why junior analysts don’t capture AI leverage, but capital allocators might

- Why platforms win even when content explodes

- Why regulation, licensing, and balance sheets matter more than brilliance

You’re not saying “ideas don’t matter.” You’re saying ideas without consequence don’t set prices.

Two clarifying principles follow directly from this distinction:

- AI drains value from reproducible cognitive work.

- Economic value rebinds at the tightest irreversible constraints, wherever they sit in the system.

Economic value signals where economic power is accumulating—but the two are not the same.

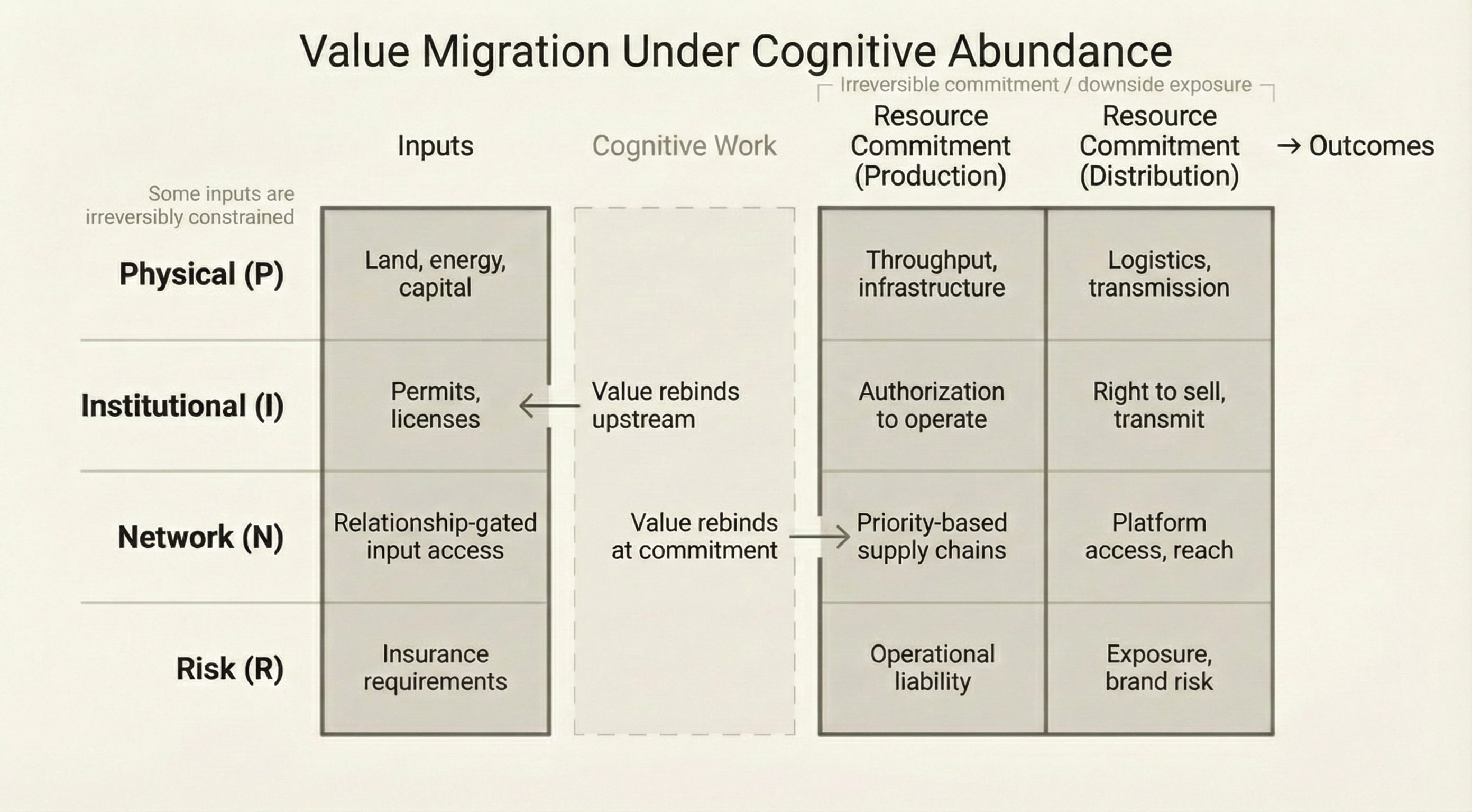

The Economic Constraint Stack

Across industries, the constraints that limit this process tend to fall into four broad categories. Together, they form what I’ll call the economic constraint stack. Each layer of the economic constraint stack governs a different way that real-world action becomes limited.

Physical constraints govern what can be produced or moved based on material limits imposed by reality itself. These constraints arise from finite capacity—such as land, energy, capital, infrastructure, compute, and time—and bind when scaling or substitution is not immediately possible regardless of intent or planning.

Institutional constraints govern what commitments are permitted under formal rules and authority. These constraints arise from regulation, licensing, accreditation, contractual obligations, and governance, and bind when action is limited by compliance rather than by capability or resources.

Network constraints govern access, coordination, and priority when participation in an ecosystem determines what can be produced, moved, or reached. These constraints arise when control is mediated by relationships, interoperability, or standing within a network rather than by ownership or permission alone. Distribution platforms are one example, but network constraints can also bind upstream through exclusive data partnerships, closed supplier ecosystems, coordinated supply chains, and contract manufacturing networks.

Risk constraints govern who bears downside when outcomes fall short. These constraints arise from liability, financial exposure, operational failure, and reputational damage, and bind when the ability to absorb loss—rather than the ability to generate ideas or plans—determines who can act.

You might reasonably ask: if the constraints in the economic constraint stack are often visible in advance, why doesn’t value remain in cognition?

Network constraints are the clearest example. Teams often know, before committing any resources, that a product will struggle to reach users, integrate into an ecosystem, or gain distribution. Those limits are frequently visible at the planning stage—as questions of positioning, audience, access, or platform fit.

But recognition is not control.

Within the economic constraint stack, network constraints only become economically binding when distribution is actually committed—through platforms, channels, contracts, or ecosystems that determine who gets access and who does not. Awareness of a bottleneck does not create leverage. Ownership of the bottleneck does.

The flow from inputs to outcomes can be summarized simply as:

Inputs → Cognitive Work → Resource Commitment → Outcomes

Artificial intelligence dramatically widens the cognitive-work layer, flooding it with low-cost output. What follows—especially resource commitment—remains constrained by physical capacity, permission, access, and accountability. The economic constraint stack describes where this flow binds once cognitive work is no longer scarce. As cognition inflates, unfinished plans accumulate upstream of the binding layer.

One implication of this shift is the rapid buildup of unfinished work. In the language of operations theory, this appears as inventory: plans, code, designs, and analyses accumulating upstream of constrained commitment. This inventory is not a failure of effort; it is a signal of a binding constraint.

The principle that follows is straightforward: when cognitive work inflates, economic power concentrates at the constraint that most tightly limits irreversible commitment at the margin.

How to Apply the Economic Constraint Stack

The economic constraint stack is not a metaphor. It is a diagnostic tool.

To apply it in any organization or industry:

- Define the outcome What real-world result is being produced—revenue, care delivered, energy generated, risk transferred, trust established.

- Map the flow Trace the path from Inputs → Cognitive Work → Resource Commitment → Outcomes.

- Identify the binding constraint Ask which layer of the economic constraint stack most tightly limits irreversible commitment at the margin:

-

- Physical (capacity, capital, infrastructure)

- Institutional (permission, regulation, contracts)

- Network (distribution, access, ecosystem position)

- Risk (liability, downside exposure, accountability)

- Locate control Who owns or governs that constraint? How is it enforced?

- Predict value capture Economic returns will concentrate at the binding layer of the economic constraint stack.

This framework explains why productivity gains in cognitive work often coexist with margin pressure—and why power shifts toward capital allocators, platform owners, regulators, and risk bearers even as intelligence becomes cheap.

Figure 1. Value Migration Under Cognitive Abundance

As AI expands the supply of reversible cognitive work, economic value drains from decision-making itself and rebinds at the tightest irreversible constraints—whether upstream in inputs or downstream in resource commitment—where outcomes become fixed and downside is borne.

Testing the Model Across Industries

A model is only useful if it holds up outside the environment in which it was conceived. To test whether the economic constraint stack reflects a general economic shift—rather than a technology-specific story—it helps to apply it to industries with very different structures. Across sectors, the specific binding layer differs—but the economic constraint stack holds.

What follows is not a comprehensive survey, but a set of illustrative cases chosen to stress-test the model across distinct economic contexts.

In healthcare, AI improves diagnosis and documentation. Yet care still occurs in physical settings, under regulation, and with legal liability. Value concentrates in care delivery systems, reimbursement pathways, and institutions that can absorb risk.

In finance, analysis becomes abundant. What remains scarce is capital, regulatory permission, trusted rails, and the ability to warehouse risk. Value concentrates in balance sheets and access—not insight itself.

In media, creative output explodes. Attention does not. Value concentrates in distribution platforms, recommendation systems, and owners of established intellectual property.

In law, research and drafting are commoditized. Authority, representation, courts, and liability remain scarce. Value attaches to those who can act under institutional permission and absorb responsibility.

In education, teaching content becomes cheap. Credentials, placement, accreditation, and trust remain scarce. Value concentrates in institutions that control signaling and access to opportunity.

Across these cases, the same pattern emerges. Artificial intelligence inflates the supply of cognitive work. Value migrates to the constraints that govern irreversible commitment and consequence. What differs is which constraint binds, and how tightly.

What This Means for Jobs

The first effect of knowledge inflation is not unemployment, but loss of leverage.

Roles built primarily around producing cognitive work—analysis, drafts, recommendations, plans, or code—become easier to substitute as supply increases. Competition intensifies. Pricing power erodes. Many people may continue to work just as hard as before, but find that their contribution commands less economic reward.

By contrast, roles closer to irreversible commitment tend to gain leverage. These include positions that control capital allocation, coordinate real-world execution, manage risk, hold authority, or bear responsibility when outcomes fail.

The result is a subtle but consequential bifurcation. Employment does not disappear, but bargaining power shifts. The risk is not mass displacement, but widespread underemployment—people working below their historical leverage despite rising apparent productivity.

This is not primarily a skills problem. It is a position-in-the-system problem.

Leverage now comes less from producing insight and more from proximity to commitment, authority, and consequence.

What This Means for Power

As value migrates, it concentrates.

Institutions that control binding layers of the economic constraint stack—physical infrastructure, regulatory permission, network access, or risk absorption—gain leverage. Platforms strengthen. Incumbents consolidate. Capital-intensive organizations become more central.

Trust changes character as well. When output is scarce, trust can be personal and reputational. When output is abundant, trust becomes institutional. It is embedded in contracts, audits, insurance, compliance regimes, and governance structures.

AI democratizes capability. It does not democratize control.

Power accrues not to those who generate the most intelligence, but to those who decide which intelligence gets acted upon—and who bears the cost when it fails.

What This Makes Possible

This is not collapse. It is reallocation.

Knowledge abundance enables real progress: faster scientific discovery, better medicine, improved systems design, and lower barriers to experimentation. The risk lies not in abundance itself, but in failing to adapt the institutions that channel it.

For individuals, the question becomes less about intelligence and more about position. Proximity to irreversible commitment—capital, authority, access, and responsibility—matters more than mastery of information alone.

For organizations, advantage flows to those that reliably turn ideas into outcomes under constraint.

For society, the choice is whether to allow this reallocation to proceed invisibly, reinforcing existing concentrations, or to redesign institutions with an explicit understanding of where scarcity now lives.

Knowledge will continue to inflate. Constraints will continue to capture value. What changes is whether we understand that process well enough to shape it.

That is the work ahead.