In my office, I have a poster on the wall. It shows every commercial airline flight and airport in the world on a single day. Hundreds of thousands of flights. Thousands of airports. A dense, glowing web that makes one thing immediately obvious:

No human could ever manage this system directly.

And that’s a good thing.

We want machines coordinating systems at that level of complexity. We don’t see that as a loss of control—we see it as progress. We trust software to route planes, avoid collisions, manage schedules, and absorb disruptions that would overwhelm any human operator.

That poster has been on my wall for years. But only recently did I realize how directly it applies to how we should rethinking how we build software itself.

Teaching AI While the Ground Is Still Moving

As an adjunct professor teaching AI—and as someone who also runs a software development company—I spend a lot of time worrying about whether I’m actually teaching students the skills that will matter when they graduate. That concern isn’t abstract. My own development practice has changed more in the last six weeks than it did in the six months before that—and more in the last year than in the several years prior.

In the past few weeks, our team has built multiple production-grade applications—complete systems with cloud databases, secure role-based access control, user and admin interfaces, APIs, and AI integrations—that previously would have taken full teams several quarters to deliver.

To be clear, this isn’t because we’ve suddenly become better coders. In fact, within the team there’s no shortage of technical depth. It wasn’t typing speed. It wasn’t clever prompting. And while agentic IDEs are improving rapidly—and the progress is genuinely impressive—that wasn’t the real source of the leverage.

It was where and when the thinking was done.

The specifications for those systems were long—150 pages in one case, and over 360 pages (and growing) in another. Not because we were trying to predict everything, but because in an AI-driven, agent-first world it finally makes sense to deliberately shift where the hardest work happens upstream.

For most teams over the last decade or two, that probably sounds foreign. Formal spec documents largely gave way to backlogs and user stories as a way to manage human cognitive limits and move faster.

What’s changed is that those limits are no longer the binding constraint.

That observation turns out to be a clue to a much larger shift—one that has less to do with tools, and more to do with the limits of human cognition itself.

None of these ideas are entirely new in isolation—but the way they come together under modern AI tooling has fundamentally changed how software actually gets built.

The Real Pivot: The World Is Too Complex for Humans

If you’re a developer or product manager, you already feel how fast things are changing. For teams that have learned how to work effectively with AI, execution time has collapsed. Iteration is cheap. The cost of generating code has dropped dramatically.

What hasn’t dropped is complexity.

Modern software systems are no longer something a single human—or even a small team—can fully reason about end-to-end. We’ve known this for a while, but we kept pretending otherwise. We optimized specifications for human consumption: short, readable, minimal. We treated detail as a smell. We assumed that if a spec was too long for a human to comfortably read, it was probably doing something wrong.

Entire bodies of work exist to teach us how to write better product specifications—and we implicitly expect individuals to absorb, remember, and apply all of it on demand.

That assumption no longer holds.

The world is too complex for humans—and now we finally have collaborators that can operate at that scale.

Once you accept that, several things follow immediately:

- It becomes rational to do far more cognitive work up front.

- It becomes rational to create specifications that are far more detailed than any human would comfortably read or reason about end-to-end.

- And it becomes rational to stop treating human readability as the primary optimization target for a well-defined system specification.

Only the core narrative of a spec—the purpose, the problem, the differentiation—is written for humans. The rest is written for machines.

In an agent-first world, the optimization target changes.

Length is not waste. Ambiguity is.

This is not about replacing human judgment. It’s about placing human judgment where it matters most.

What Intentional Coding Actually Is

I use the term intentional coding not to describe a new style of implementation, but to name a shift in where the most consequential work of software development actually happens.

The hard part of building software no longer lives in writing code. It lives in deciding—explicitly and irreversibly—what that code is allowed to become.

Good engineers have always known that intent matters; what’s changed is that intent now has to be captured explicitly in specifications detailed enough for machines to execute against—and that the cost of researching, validating, and refining that intent up front has collapsed.

Intentional coding deliberately pushes the hardest cognitive work forward. It uses AI as a reasoning partner to help surface, test, and commit intent into specifications that go well beyond what a human could reasonably hold in their head.

It’s worth clarifying what this is not. This isn’t a faster way of coding, and it isn’t what’s often described as “vibe coding,” where intuition and rapid generation drive development and structure emerges—if at all—after the fact. Intentional coding uses intuition early, but then forces that intuition through explicit structure and irreversibility-aware decisions before large amounts of code get generated.

From there, coding agents can take on much of the repetitive, mechanical, and debugging-heavy work—the slow, monotonous parts of implementation—while human developers stay focused on judgment, tradeoffs, and decisions that are hard to reverse.

A Note on How the Spec Gets Written

I’m going to assume most readers already know how to prompt an LLM to produce a detailed, human-readable document. This article isn’t about prompting mechanics, and I’m not going to share prompt recipes.

What matters more is how the thinking happens before the spec exists—how AI is used not just to draft documentation, but to help shape strategy, test assumptions, and absorb work that was previously pushed downstream: deep research, structural validation, assumption-testing, and simulation of users, workflows, and failure modes, and pressure-testing decisions whose cost of reversal grows rapidly once implementation begins.

When I work on these documents, I rarely sit at my desk. I turn on audio mode in a mobile LLM—any modern system works—and I move. I walk. Often for an hour or two.

There’s good evidence that physical movement improves divergent thinking, abstraction, and associative idea generation—exactly the modes you need before committing intent to a specification. Before you can write a document that governs a system, you have to form a coherent mental model of what that system is, why it should exist, and which decisions deserve to be made irreversible.

During these walks, I treat the AI as a thinking partner, not a typist. I’ll alternate between:

- asking it to research best practices and analogous systems,

- having it challenge my assumptions or take a contrarian view,

- bouncing half-formed ideas off it to see what sticks,

- and simulating how customers might react to proposed workflows or value propositions.

I’m deliberately glossing over some of the more technical techniques here—not because they’re proprietary, but because they’re secondary to the shift in where the thinking happens.

This is also where I deliberately sharpen my thinking by applying conceptual frameworks—lenses for reasoning about products, adoption, and strategy.

I don’t expect myself to remember every framework in detail. That’s not realistic. Instead, I treat frameworks as framing devices—ways of forcing better questions at the right moment—and rely on the agent to recall and apply the details when they’re actually needed.

For example, if this is a genuinely new-to-the-world product, I’ll often ask the agent to walk me through an Imaginable-style exercise, based on Jane McGonigal’s work, to explore not just what the product does, but what kind of future it implies—and whether that future is actually compelling.

If I’m worried about adoption risk, I’ll ask the agent to apply Everett Rogers’ Diffusion of Innovations framework and tell me which features, onboarding elements, or early-user affordances I might be underweighting for early adopters. If I’m entering an established market, I’ll often reach for Clayton Christensen’s Innovator’s Dilemma lens to stress-test whether we’re actually entering the market with a feature scope that makes sense—or just building something technically clever that won’t move the needle.

Other times I’ll pull in customer onboarding frameworks, models that surface network effects and cold-start dynamics, or pricing frameworks that directly shape feature decisions. Some frameworks are better suited to new products, others to extensions of existing ones. The point isn’t to apply all of them. It’s to know which ones to reach for—and when.

This has become one of the most critical new skills for both product managers and developers: becoming a curator of framing devices, not a memorizer of rules. These days I read widely, keep the frameworks I find most useful on a dedicated shelf in my office, and selectively apply them—often scanning titles, asking the agent to apply a given lens, and then jointly discussing what surfaces.

I’ll do this across multiple sessions, sometimes for hours, not to finalize answers, but to hone my thinking and look for a small number of critical “black swans”—insights that quietly determine whether a product succeeds or fails.

Once that exploration stabilizes, I tell the agent explicitly: “OK, we’re writing a specification now.” I ask it to outline the document, and from that point forward, I keep returning to the same question:

What is the next most critical, differentiating, or irreversible decision this product requires us to make—and commit to?

That question determines what gets written next, what becomes an appendix, and where execution should begin.

That shift demands a different way of structuring intent.

Island-Hopping Spec Design

Before diving into the details of the actual spec writing, it helps to see the terrain.

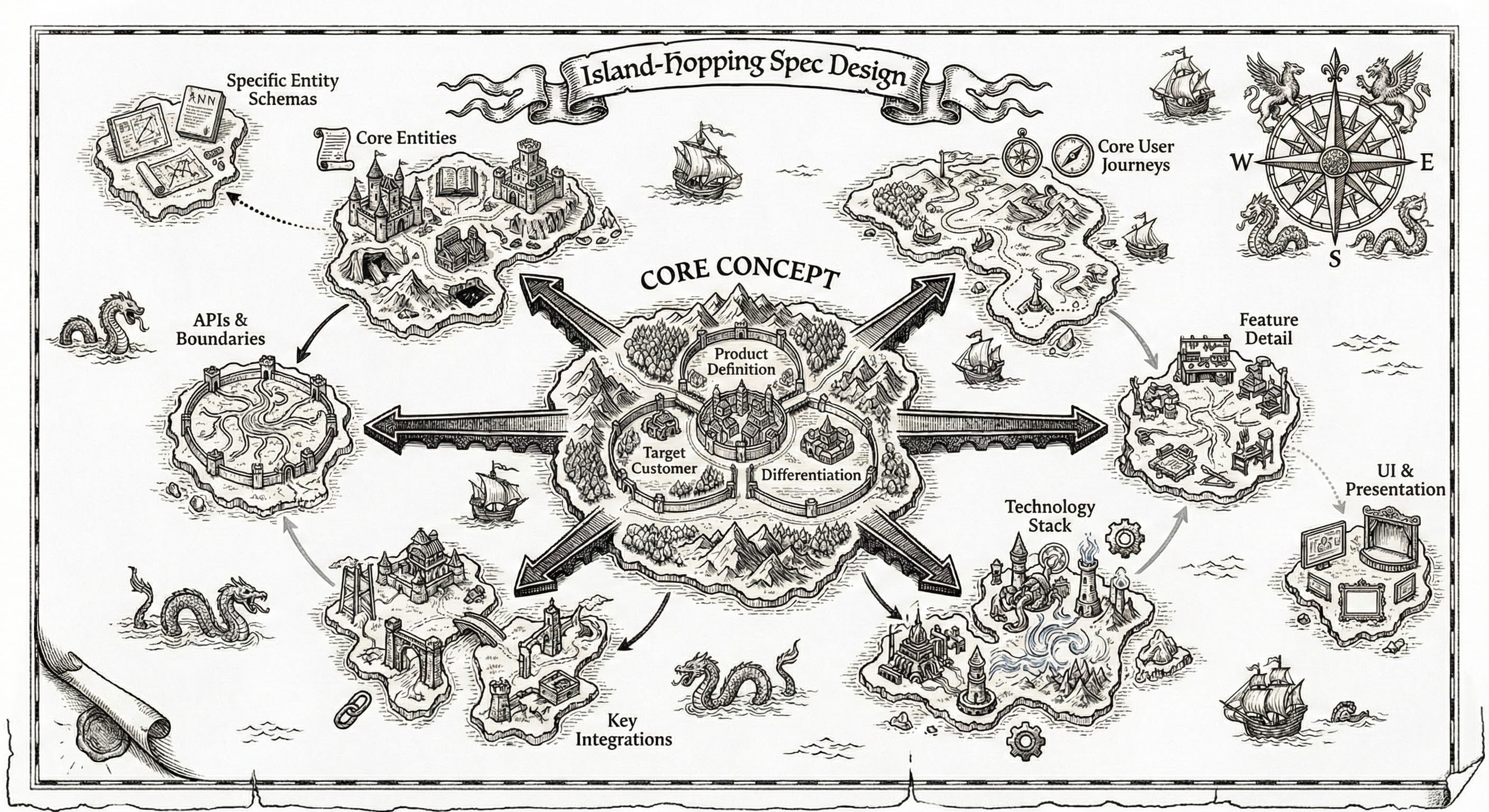

Figure: Island-Hopping Spec Design. The central island represents non-negotiable product intent. Surrounding islands represent decisions ordered by irreversibility, expanding outward from what is hardest to change to what is easiest. The governing principle is irreversibility, not sequence. This is a map of risk, not a timeline.

The core method I use for practicing intentional coding is something I call Island-Hopping Spec Design.

The metaphor comes from history, but it’s really about systems. In the Pacific theater of World War II, planners didn’t try to capture everything at once. They focused first on the islands that controlled movement, supply, and influence—and only then expanded outward.

Specification works the same way.

You do not spec everything at once. You start with the decisions that are hardest to undo and expand outward from there.

This ordering is not driven by dependency alone. It’s driven by irreversibility.

Prioritizing by Irreversibility, Not Just Dependency

Some decisions are cheap to change. Others are devastating to revisit.

The most irreversible decisions belong at the center of the spec. The least irreversible belong at the edges.

There are a few things that are effectively non-negotiable. Defining the problem you’re solving, the target customer, and the product’s differentiation always belongs at the center. Changing these late isn’t just expensive—it’s often fatal to the product.

Core entities and core user journeys almost always emerge early as well. They define what exists in the system and how value is created. Once those are set, everything downstream takes shape around them.

Beyond that, the ordering becomes highly product-specific.

UI is a good example. Historically, many teams started there because UI produces fast, visible progress and externalizes complexity—a picture really is worth a thousand words. That ordering made sense when humans had to carry most of the system’s complexity themselves.

Intentional coding reorders decisions around irreversibility instead. In many systems, that naturally pushes UI further out, because it depends on underlying entities, behavior, and constraints. Defining it too early often leads to repeated rework as the system evolves.

But that’s not a rule.

For products where UI is the differentiator—consumer-facing products, design-led tools, or workflow-heavy systems—UI decisions can be far more costly to revisit and may belong much closer to the center. The deciding factor isn’t convention; it’s how costly a change would be later.

The same distinction applies to data. Identifying what kinds of entities exist is usually irreversible and belongs early. Defining every field, validation rule, or storage detail is far more reversible and can safely come later.

A first ring of high-impact islands typically includes:

- Conceptual model and ontology (what exists, what it means, and how it relates)

- Core user journeys (how value is created)

- Interaction model and network effects (who interacts with whom, and how value compounds)

- Trust and authority boundaries (who can do what, and why)

- Technology stack constraints, including opinionated frameworks

- Key integrations

These decisions shape everything downstream and are expensive to undo.

Further out are islands that are important but more reversible:

- APIs (often designed specifically to reduce irreversibility)

- Detailed schemas and data shapes

- UI specifics (unless UI is the differentiator)

- Secondary features and optimizations

The exact ordering will vary by project. The method matters more than the map. You have to understand your own landscape well enough to identify which decisions are truly strategic and which ones can safely wait.

This is what intentional coding looks like in practice.

Specs That Match the Model

This ordering dictates how the spec itself is structured.

The main specification—often 10–20 pages—is written for humans. It captures intent: the problem, the audience, the differentiation, and a high-level system view. It’s stable. It rarely changes.

Everything else lives in detailed appendices.

Each appendix corresponds to an island. They’re modular, swappable, and designed for selective consumption by AI agents. A detailed table of contents becomes an interface: you give an agent the structure, ask what it needs, and provide only the relevant sections.

For example, one appendix might define the existence of core entities without detailing every attribute. Later appendices can expand individual entities in depth. High-level clarity enables incremental precision.

In one recent project, the specification eventually grew to appendices A through P. Coding began around Appendix G.

That’s not a failure of planning. That’s the system working.

When Coding Starts (and How It Starts in an Agentic Workflow)

This is not “big design up front.” And it’s also not a free-for-all where agents immediately start generating UI because that’s what produces fast, visible output.

In practice, coding begins once you’re two or three layers deep—once the most irreversible decisions are locked. But how you begin matters just as much as when.

The way I start is by adding a two-tier table of contents to the specification—essentially exposing just the H1 and H2 structure of the document. This gives a high-level map of the system: the core concepts, major domains, and appendices, without burying the agents in detail.

This table of contents isn’t meant to be read end-to-end. It’s a navigation and reasoning aid.

I then feed the agents:

- the main body of the document, and

- the two-tier (H1/H2) table of contents

and ask a very specific question:

If our goal is to de-risk this product, where would you recommend starting?

This step is important. Many agentic IDEs are optimized to jump quickly to UI, because UI produces immediate, human-satisfying progress. I strongly recommend not taking the candy unless UI is genuinely one of the most irreversible or differentiating aspects of the product.

Once we agree on which island to start with, I tell the agents to proceed—but with three explicit instructions.

First, I ask them to create a separate features document. This document exists primarily for later human consumption. As features emerge during development, they get logged there rather than immediately forcing changes back into the core specification.

Second, I ask them to create an open questions document. This is a place to record questions where developers are perhaps 70–80% confident in the answer, but want that judgment checked later. Importantly, the existence of an open question does not block development. Developers are expected to proceed using their best judgment and document the uncertainty rather than freezing progress.

Finally, I ask the agents to prompt me for the specific sections and appendices they believe they need to begin work. At that point, I share:

- the sections they requested, and

- any additional sections or appendices I believe are relevant, even if the agent didn’t explicitly ask for them.

As development proceeds, we occasionally encounter areas that clearly deserve their own appendix. When that happens, I stop and create a new appendix, fleshing out that detail in isolation. This works precisely because the core body of the document is not so detailed that it needs to be rewritten every time something new emerges.

Sometimes the agents will suggest features that would be genuinely nice—but not nice enough to justify rewriting even an appendix. In those cases, we still build the feature, but we simply record it in the features document.

The combination of features and open questions turns out to be a powerful pattern. It allows execution to move quickly without constant back-and-forth with product management, while still capturing uncertainty and intent so it can be reviewed later with full context.

This is also where a critical developer muscle gets exercised. In an agentic environment, developers who simply implement exactly what they’re told—without applying judgment—will not survive.

In many ways, this helps explain why we’ve already lost so many entry-level roles. Those jobs were often built around executing well-defined tasks with limited autonomy. As AI systems absorb more of that work, the remaining value shifts sharply toward judgment, prioritization, and the ability to proceed responsibly in the presence of uncertainty.

Intentional coding assumes and requires that developers think, decide, and document uncertainty rather than waiting for perfect instructions.

Intentional coding doesn’t delay execution. It creates a structure where agentic execution can move fast without quietly accumulating irreversible risk.

A Note on Team Size and Intentional Simplification

I’ve described this process in a simplified form to keep the concepts clear. What I’ve outlined here reflects how intentional coding works most cleanly in small teams, where decision-making, execution, and feedback loops are tightly coupled.

That’s not a limitation—it’s the point. Small teams are where the leverage of this approach is easiest to see. When the same people are responsible for judgment, execution, and outcomes, shifting the hard thinking upstream produces immediate, compounding benefits. Agentic tools amplify that effect by absorbing execution work while humans stay focused on the decisions that actually matter.

Larger teams can—and should—adapt these ideas, but the adaptations are mostly about coordination, not philosophy. You’ll need clearer ownership of appendices, more explicit decision boundaries, and stronger norms around how and when irreversible decisions get made. The core principles don’t change: prioritize by irreversibility, expand outward from the most consequential decisions, and use the specification as the shared surface for intent.

What I’m describing here isn’t a prescriptive org model. It’s a way of placing human judgment where it has the highest leverage. Small teams are simply the environment where that placement is easiest to see—and easiest to get right.

The Skills That Matter Now

Putting my professor’s hat back on, this is the question I care most about: given where software development is headed—with AI coding agents increasingly handling execution, and approaches like intentional coding and island-hopping spec design reshaping how we decide what gets built—what skills will actually matter for developers going forward?

The answer is more hopeful than it might initially sound.

As execution becomes cheaper and more automated, the value of developers doesn’t disappear—it shifts. The skills that endure are the ones that help teams decide what should exist, why it should exist, and how to proceed responsibly when certainty is incomplete. AI coding agents change the economics of execution, but they don’t eliminate the need for judgment. In fact, they make that judgment more visible—and more valuable.

Skills that matter more:

- Problem framing and differentiation — clearly articulating what problem is worth solving and why this solution is meaningfully different

- Systems thinking — understanding how parts interact, where complexity accumulates, and how changes propagate

- Domain modeling — defining what exists in the system and what those things mean

- Specification craftsmanship — expressing intent clearly enough that both humans and agents can reason over it

- Judgment about irreversibility — knowing which decisions are expensive to undo and deserve early attention

- Architectural foresight — designing boundaries that enable change rather than resist it

- Framing-device curation — knowing which conceptual lenses, frameworks, or models to apply at the right moment, and relying on agents to recall and apply the details rather than memorizing them

- Human–AI collaboration literacy — knowing how to guide, challenge, and verify agentic systems rather than blindly accept their output

At the same time, some skills matter less—not because they’re unimportant, but because they’re no longer scarce.

Skills that matter less:

- Syntax memorization

- Tool-centric identity as a primary differentiator (e.g., “I’m a React dev,” “I’m a Spring Boot developer”)

- Boilerplate coding

- Debugging by brute force

- Premature UI definition

- Process compensating for unclear intent

Those skills aren’t gone. They’re just no longer the bottleneck.

One natural question this raises is whether this blurs the traditional line between product management and development. In practice, what’s changing isn’t that roles collapse, but that judgment gets redistributed. Developers are increasingly expected to exercise local product judgment—making tradeoffs, documenting uncertainty, and proceeding responsibly without perfect instructions.

For example, deciding whether to ship a constrained version of a feature now, delay it until core workflows are clearer, or expose it behind a limited interface—and recording the risks of that choice rather than escalating every decision back to product—has become part of the developer’s role. In an agent-first environment, making these decisions quickly is often the only way to keep execution speed aligned with the pace of definition, and the risk of being slightly wrong on a small, reversible decision is usually lower than the risk of slowing the system down.

Strong product managers, in turn, spend more of their time on global intent, market-level irreversibility, and long-horizon decisions—setting the boundaries within which this local judgment can safely operate.

This shift also places a responsibility on senior leaders. If developers are expected to exercise judgment, managers have to stop treating them like worker bees executing pre-chewed tasks. Teams don’t develop this muscle by being shielded from ambiguity—they develop it by being trusted with it, coached through it, and held accountable for decisions, not just output.

For developers willing to adapt, this opens up a more interesting and durable role. In an AI-native world, the developers who thrive won’t be the ones who execute instructions fastest, but the ones who know what’s worth executing in the first place.

What Changed (and What Didn’t)

What changed isn’t the need for software, or for developers. What changed is where scarcity lives—execution (coding and debugging) is cheap, but intent, clarity, and judgment are not.

In a world too complex for humans to reason about end-to-end, the most important code you write is no longer the code itself. It’s the specification—written for an agent-first world—that determines what all that code becomes—and which decisions are made deliberately once, rather than being rediscovered and re-decided throughout implementation under the banner of “flexibility,” a pattern that emerged to cope with human cognitive limits.

That shift doesn’t diminish the role of developers. It re-centers it on the work that actually matters.

And that’s a good thing.