Artificial intelligence has crossed a practical threshold. Not in a speculative or philosophical sense, but in an economic one.

For the first time, machines can reliably produce knowledge work at scale: code, writing, images, music, video, analysis, and strategy. They can do it faster than humans, cheaper than humans, and at near-zero marginal cost.

That matters because knowledge work is what most people trade for money.

It’s common to describe AI as a productivity revolution, and that description is correct. But it’s also incomplete. Productivity and the inflation of knowledge work are two sides of the same coin.

Productivity, by definition, is good. It means doing more with less. It means progress and abundance. But productivity also changes value.

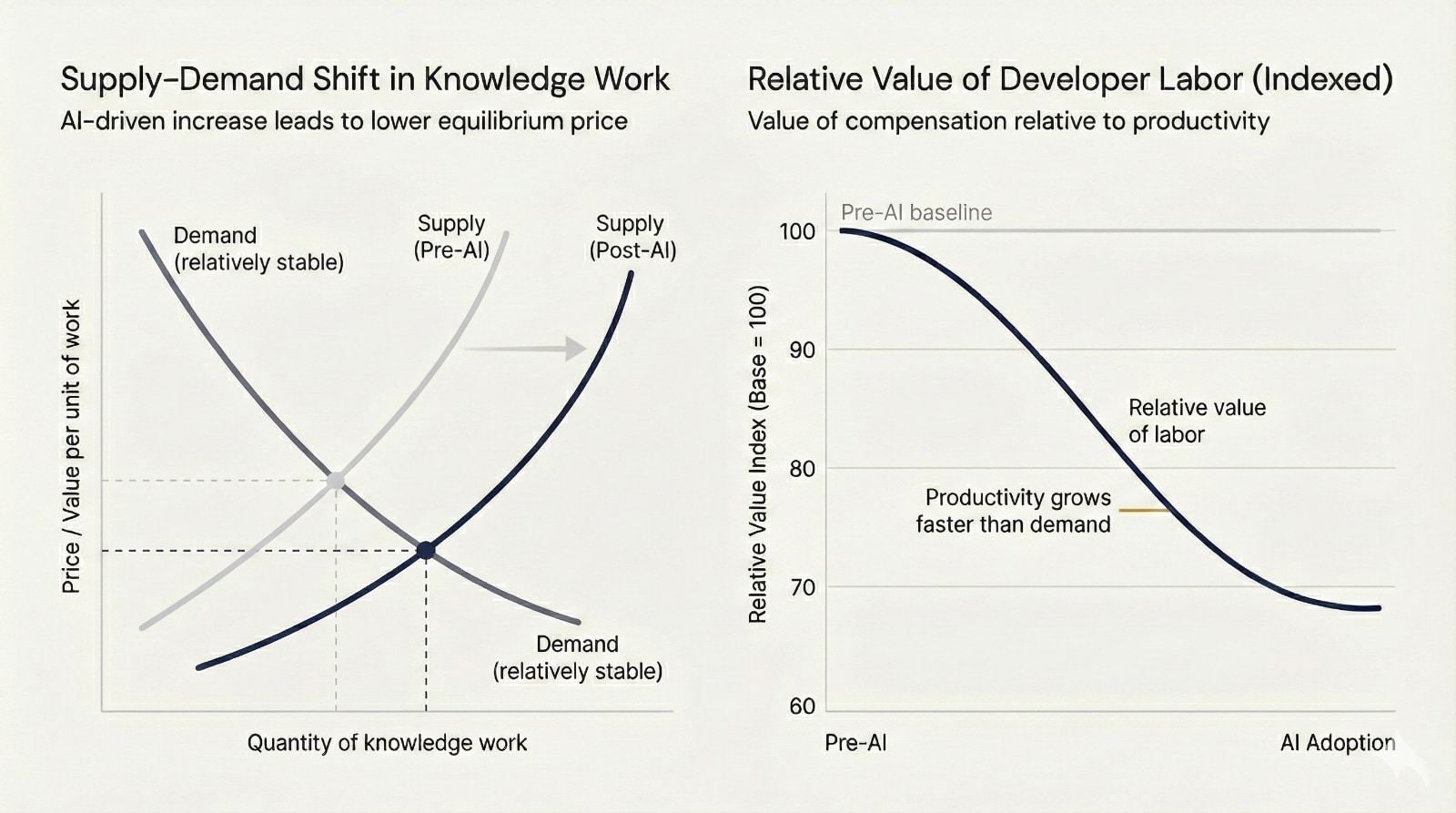

When the supply of something increases faster than demand, each unit becomes worth less. That’s not a metaphor—that’s the basic mechanics of inflation.

The exact magnitude of this decline will vary by role and market, but the direction is unavoidable: when productivity outpaces demand, the relative value of labor falls.

Side-by-side charts:

- Left: Supply–demand shift in knowledge work (mechanism)

- Right: Relative value of developer labor over time (consequence)

Developers Are the Canary — Because They Tried It First

Those of us in software development felt this shift early, not because we’re fragile or uniquely exposed, but because we were the first to apply the tools directly to our own work.

AI didn’t arrive as a white paper or a strategy memo. It arrived as autocomplete—embedded directly into the tools developers already used. We tried it immediately, on real problems, and the impact was obvious within days.

AI-assisted coding tools now routinely claim productivity gains of 50% to 80% for many tasks. Entire features that once took weeks can now be implemented in days or hours. One developer can often do the work of several.

That is genuinely impressive.

But it hides an economic assumption we rarely say out loud.

If developers can produce software 80% faster, then to preserve salaries at scale, one of two things must be true: either the world must suddenly have demand for roughly 80% more value-producing software, or developers must capture the productivity gains themselves.

History suggests neither is likely.

Demand is not for “code” in the abstract. Demand is for products, features, and outcomes. And recent labor-market signals suggest that demand is not expanding in proportion to productivity.

Over the past two years, job postings for software developers and related roles have declined meaningfully across major hiring platforms, even as AI adoption accelerated. LinkedIn and Indeed both reported double-digit percentage drops in tech job postings during 2023–2024, while many firms publicly cited “doing more with smaller teams” as an explicit justification for reduced hiring. At the same time, several large technology companies reported flat or shrinking engineering headcount while continuing to ship more features, often pointing directly to AI-assisted workflows.

Lower costs do increase experimentation—we are seeing more prototypes, more internal tools, more short-lived projects—but they do not create infinite demand.

Most organizations do not suddenly need 80% more dashboards, internal tools, features, or bespoke systems. There are real limits: customer attention, product complexity, maintenance burden, coordination costs, and plain human sanity.

When productivity grows faster than real demand, value compresses. Fewer people are needed to produce the same outcomes. Expectations rise. Salaries stagnate or flatten.

This is not new. It is the same pattern seen whenever automation increases throughput faster than markets expand. Productivity does not automatically raise wages. It lowers the cost of output.

Developers aren’t special. They’re early.

This Is Not Just a Software Story

What’s happening in code is now spreading across the entire knowledge economy.

Writing came next. AI can now generate fluent articles, reports, and marketing copy instantly. The internet is filling with competent text. Not better text—cheaper text.

Recent advances in image generation from major research labs now produce images that reflect composition, style, intent, and spatial coherence—without requiring users to do most of the creative work themselves.

This isn’t assistance. It’s generation.

Music crossed the same threshold. Tools like Suno can now generate complete songs—structure, vocals, and emotional arc—from a sentence. These aren’t demos. They’re finished tracks, produced in effectively infinite supply. In a striking recent example, an AI-generated country song, “Walk My Walk” by the virtual act Breaking Rust, reached No. 1 on Billboard’s Country Digital Song Sales chart in the United States, illustrating how quickly algorithmically generated music is entering mainstream recognition.

Video is close behind. Editing, scripting, scene generation, and even synthetic actors are moving from novelty into standard workflows.

Law is already there. Contract review, legal research, and first-pass drafting are increasingly automated. Firms don’t bill for hours that no longer exist, which is progress unless you were billing those hours.

Across every one of these fields, the pattern is the same: output increases rapidly, barriers to entry fall, supply overwhelms demand, and unit value declines.

This isn’t about talent disappearing. It’s about scarcity disappearing.

Creativity Is Not the Safe Harbor People Hope It Is

At this point, someone usually says, “Yes, but humans still have creativity and judgment.”

That’s true—for now.

But it’s not a long-term refuge. NanoBanana Pro doesn’t just execute instructions; it makes compositional decisions. Suno doesn’t just generate sound; it structures music.

AI isn’t merely copying anymore. It’s learning to originate within constraints, which is how much human creativity actually works.

Creativity and judgment remain valuable in the medium term, but they are not permanent moats. They buy time, not immunity.

Building a career around what AI can’t do yet is a fragile strategy.

Trust Becomes Valuable — Temporarily

During inflation, people anchor to trust. That applies here as well.

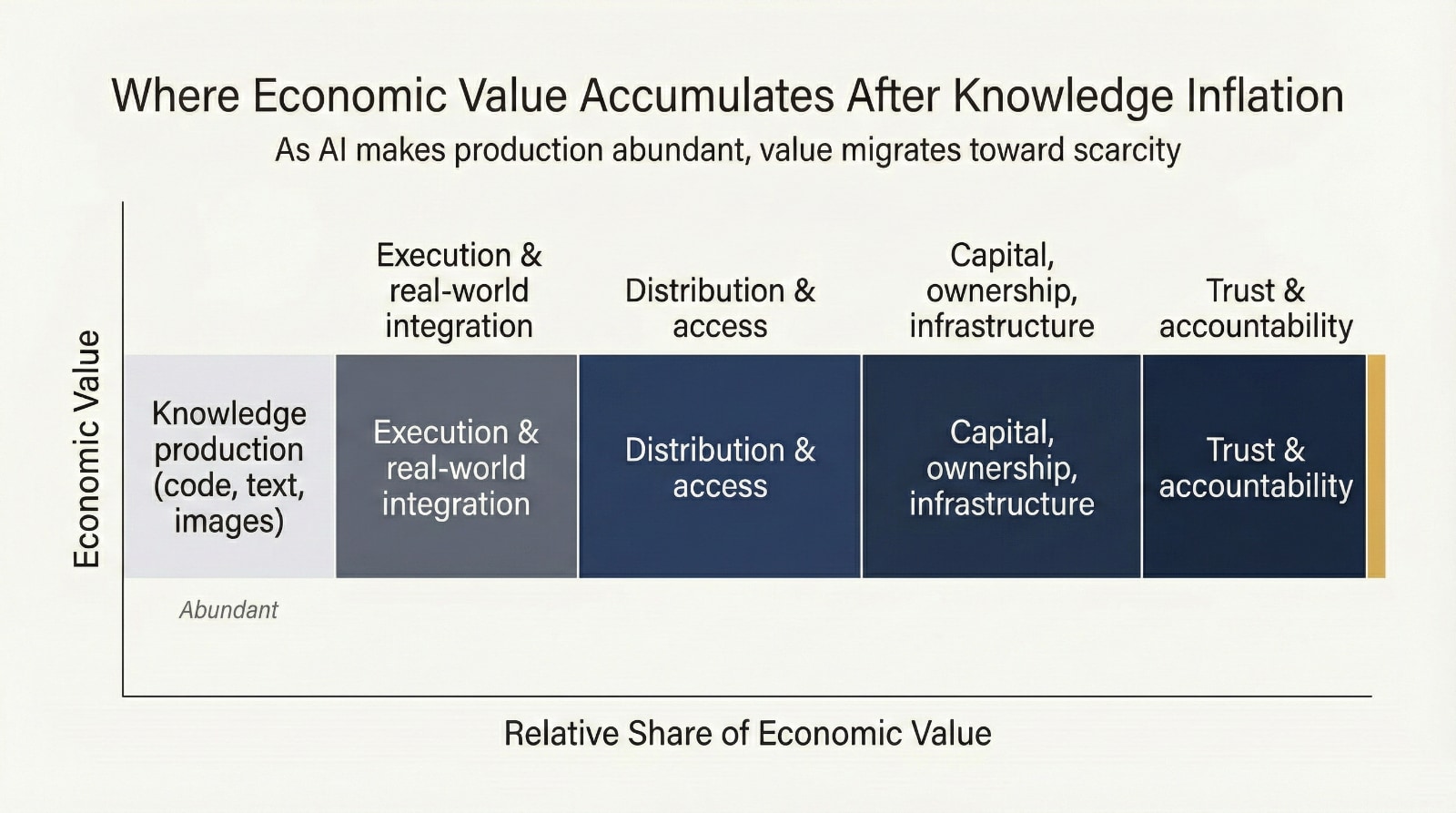

When output becomes abundant, people stop paying for what is produced and start paying for who stands behind it. Trust matters because AI can generate answers, but not accountability. It has no reputation and no responsibility.

In unstable systems, trust stabilizes value. That’s why relationships, credibility, and judgment matter more right now.

But even this has limits. Trust signals can be simulated. Reputation can be automated. Accountability can be abstracted.

Trust isn’t the destination. It’s the bridge.

When production becomes abundant, value doesn’t disappear—it relocates. It moves away from raw output and toward whatever remains scarce: execution in the real world, control of distribution, ownership of infrastructure, and trust that still carries accountability. This isn’t a moral judgment. It’s the same pattern markets follow every time abundance arrives.

Value migration in an AI-abundant economy (illustrative)

The Upside Is Real

This is not only a story of erosion. AI is also delivering genuine breakthroughs—and in some domains, the upside is hard to overstate.

Protein folding is a clear example. For decades, understanding protein structure resisted human effort and constrained progress across biology, medicine, and materials science. Then AI models like AlphaFold arrived and effectively solved the problem at scale.

The result wasn’t marginal efficiency. It was a structural leap forward. Drug discovery accelerated. Medical research moved faster. New proteins could be designed rather than merely discovered, opening doors to novel therapeutics, industrial enzymes, advanced adhesives, and entirely new classes of materials. Some researchers estimate that this single breakthrough advanced parts of the field by as much as twenty years in a matter of months.

This is what abundance looks like when applied to discovery rather than labor substitution.

The same pattern is now emerging in product innovation. Simulation, testing, and iteration increasingly happen before anything is built in the real world. Ideas can be explored, stress-tested, and discarded cheaply. Risk moves upstream. Failure becomes inexpensive. Progress compounds.

In other words, while AI compresses the value of some forms of work, it dramatically expands the frontier of what is possible.

This isn’t collapse. It’s transformation.

The Question We’re Avoiding

This is not a skills problem. You cannot out-skill a supply shock.

In the short term, it makes sense to learn to work with AI, focus on outcomes instead of outputs, and build trust while it still matters.

But the real issue is larger.

If knowledge work is no longer scarce, what are we actually trading for money? Why do we work at all? And how do we distribute value in a world where productivity no longer requires people in the same way?

Those are not technical questions. They are social ones.

This essay is about recognizing that shift while it’s still unfolding.

We won’t be able to answer the bigger questions clearly if we keep pretending this is just a productivity upgrade.

It isn’t.

Productivity and the inflation of knowledge are two sides of the same coin. And once you see it that way, everything else starts to make sense—whether you’re ready for it or not.